Crypto’s Dual Reality in Central Asia

September 16, 2025

Central Asia is undergoing a financial experiment unlike any other region. On one hand, governments are racing to formalize digital asset markets with licensing frameworks, institutional pilots, and state-backed initiatives. On the other, the majority of actual trading volume continues to flow through informal peer-to-peer (P2P) and over-the-counter (OTC) channels, deeply rooted in local cash economies. This dual reality—formal regulation and informal resilience—defines the region’s crypto landscape today.

Regulation Meets Reality

Kazakhstan has emerged as the region’s most ambitious regulator. Through the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) and its financial authority AFSA, the country has introduced laws on digital assets, mining taxation, and even pilots such as a Bitcoin ETF. These steps were meant to showcase Kazakhstan as a global hub, yet licensing has been unstable: Binance and Bybit both received approval only to see it later withdrawn, leaving uncertainty around the regulatory perimeter.

Uzbekistan has taken a different route, embedding crypto into its banking sector. The National Agency for Perspective Projects (NAPP) oversees a system where banks like Kapitalbank and Octobank dominate the licensed market. Here, adoption looks less like a retail-driven boom and more like a cautious integration of digital assets into the financial mainstream.

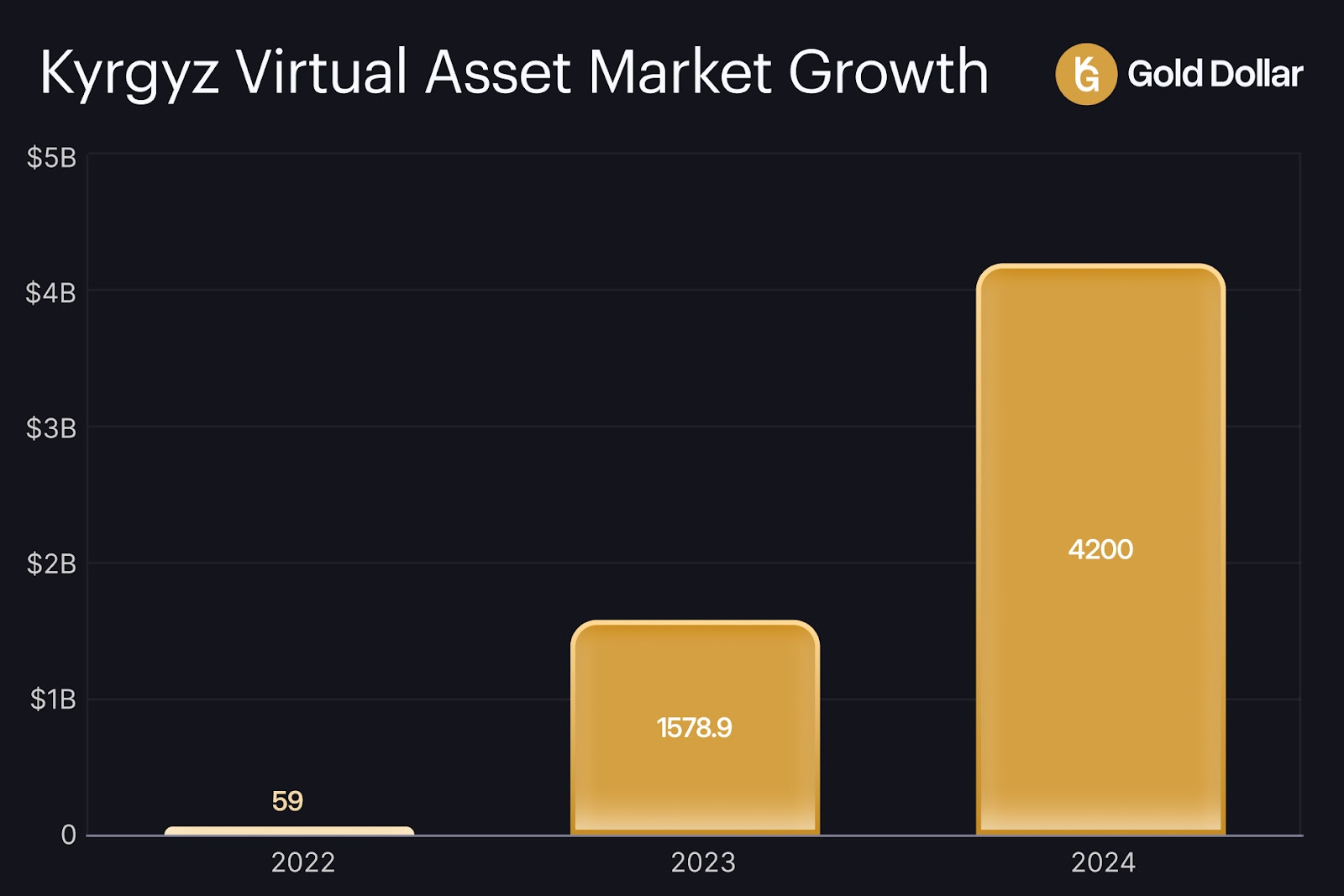

Kyrgyzstan, meanwhile, has moved quickly to issue licenses for exchanges and mining operators. At one point in 2024, over 120 firms were officially registered. This surge in formal activity is mirrored by explosive market growth: from just $59M in 2022, the Kyrgyz virtual asset market expanded to $1.58B in 2023, and surpassed $4.2B in 2024.

Yet beneath this headline growth lies a striking concentration: a handful of players dominate tax contributions, while grassroots users still prefer Telegram brokers and informal rails.

Then there are Tajikistan and Turkmenistan—countries where formal frameworks barely exist. Crypto remains in a legal gray zone or outright prohibited, yet P2P trading persists through cross-border accounts and private OTC desks.

The Geopolitical Layer

Central Asia’s crypto policies cannot be separated from its geopolitical position. Kazakhstan, wedged between Russia and China, has used crypto to reinforce its identity as a financial hub that bridges East and West. Uzbekistan, with its bank-led model, reflects a state-centric approach aligned with its broader economic strategy of gradual liberalization. Kyrgyzstan’s rapid-fire licensing, by contrast, shows how smaller economies sometimes use regulatory agility to attract capital flows, even if enforcement lags behind.

As Kyrgyz Prime Minister Adylbek Kasymaliev put it in a recent interview with Cointelegraph:

“For landlocked states like ours, digital technologies are the best road to external markets. Our priority is human capital, which will allow us to move from a resource-based economy to one of knowledge and innovation.”

This statement captures the broader ambition behind Central Asia’s digital asset experiments: they are not just about speculation, but about carving out access to global markets in spite of geographic and structural constraints.

For Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, the lack of progress also tells a story: geopolitical caution. Both states remain heavily reliant on Russian financial ties and wary of opening space for foreign-dominated digital platforms.

At the same time, China’s Belt and Road Initiative looms large. Central Asia is a key corridor for trade infrastructure, and digital finance is becoming part of that equation. Crypto adoption here is not just about speculation—it is also a hedge against currency volatility, remittance friction, and dependence on the US dollar.

Mining and Energy Dynamics

Energy is another axis of Central Asia’s crypto duality. Kazakhstan became one of the world’s top Bitcoin mining destinations after China’s 2021 ban, thanks to cheap coal-powered electricity. But the boom quickly strained its grid, forcing the government to impose special tariffs on miners and cut illegal operations. Mining has since declined, yet the episode revealed how crypto can reshape national energy politics almost overnight.

Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan have also attracted miners, though on a smaller scale. Both face the same tension: mining revenues promise tax income and foreign exchange, but they also worsen electricity shortages in countries already struggling with outdated grids. In winter months, when blackouts are common, miners become politically unpopular and subject to sudden crackdowns.

This energy dimension makes Central Asia’s crypto market distinct from purely financial hubs. Here, digital assets are tied to tangible infrastructure—coal plants, hydropower stations, and regional energy politics—creating a uniquely physical layer of risk and opportunity.

The Informal Backbone

Despite state-led efforts, the real liquidity of Central Asia still flows through informal channels. In Kazakhstan, cash-based P2P markets represent over three-quarters of the $1.7 billion on/off-ramp activity. In Kyrgyzstan, a single OTC operator accounts for two-thirds of the entire cash flow. Even in Uzbekistan, where banks dominate, nearly half of all P2P volume still comes from informal cash merchants.

These systems are resilient because they are simple. Telegram brokers, OTC agents, and cash merchants can operate outside the reach of regulators, adapt quickly to local demand, and integrate seamlessly with remittance corridors. For many citizens, they remain more trustworthy than distant state institutions.

This resilience also highlights the dual reality: formal markets may offer transparency and compliance, but informal markets offer access, speed, and familiarity.

Implications for USDKG

This dual reality is precisely the environment where a gold-backed stablecoin like USDKG can thrive. The project positions itself as a hybrid solution—rooted in physical collateral and regulatory frameworks, yet flexible enough to integrate with informal liquidity rails.

- For regulators, USDKG demonstrates how digital assets can be tethered to real-world value and transparent auditing, addressing concerns of volatility and illicit flows.

- For informal markets, it offers a stable settlement layer that can coexist with OTC and P2P channels, making cross-border remittances and trade settlements more efficient.

- For enterprises, it bridges two worlds: compliant enough for institutional use, yet liquid enough to function in the shadow-dominated ecosystems that characterize Central Asia.

In this sense, Central Asia is not just a case study of fragmented crypto adoption—it is the ideal testbed for USDKG’s mission. The region shows that trust in digital money is built not only through regulation but also through cultural familiarity and resilience of informal systems. A gold-backed stablecoin can provide the missing link: credibility without sacrificing usability.

Bridging Two Realities

Central Asia’s crypto economy embodies a paradox. It is at once highly regulated and deeply informal, institutionally ambitious yet structurally grassroots. Energy shortages, geopolitical positioning, and the persistence of cash economies shape adoption in ways that make the region unique on the global crypto map.

For investors and policymakers, the lesson is clear: to understand Central Asia, one must look beyond the official exchanges and licenses and study the informal rails that carry real liquidity. For innovators like USDKG, the opportunity lies in bridging these two realities—anchoring digital assets in physical value while embracing the resilience of local adoption channels.

.svg)

-pichi.jpg)

_mini.png)